Ten years later - from Hype to Hard Reality

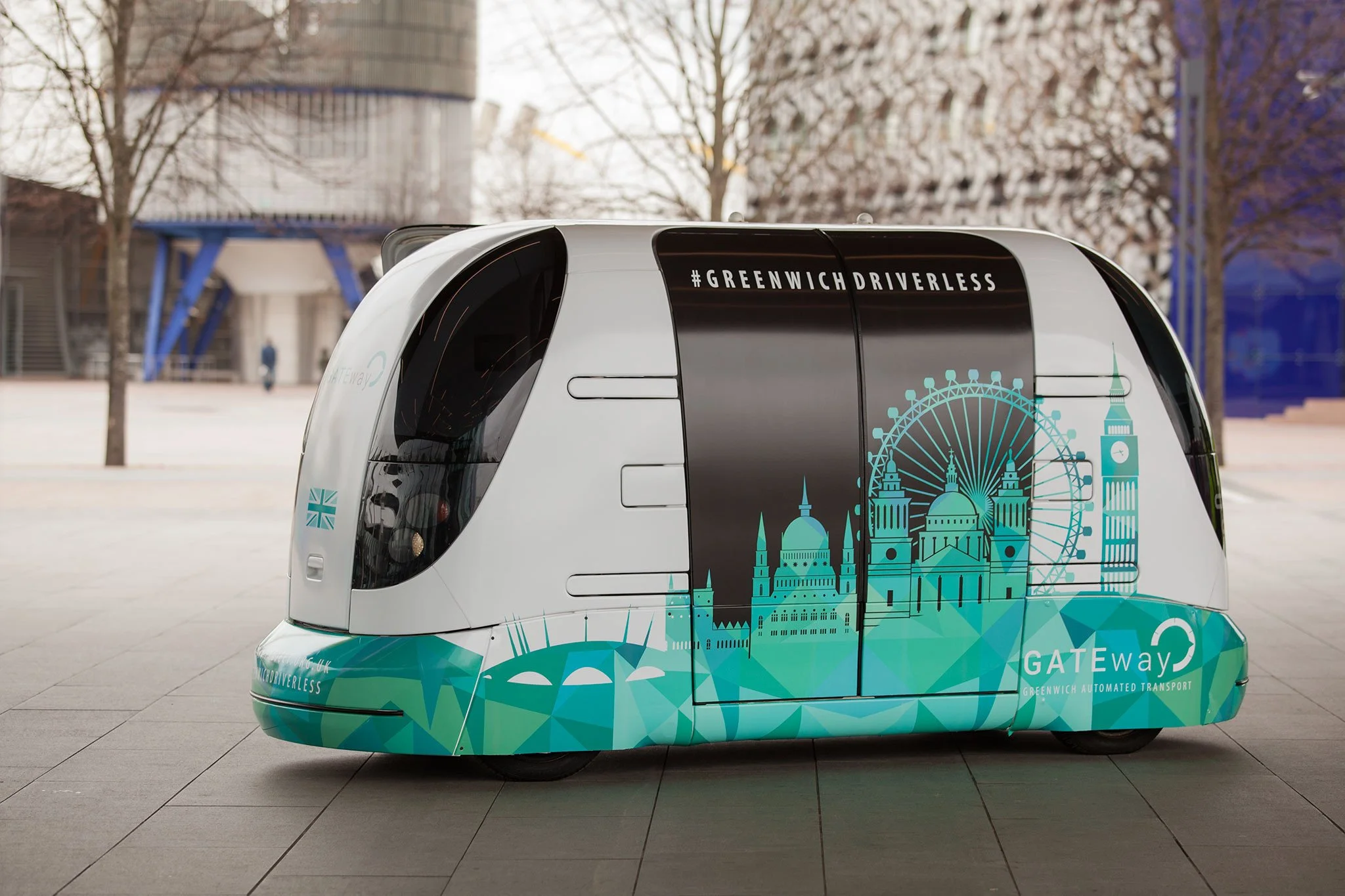

Were the flagship government-funded automated vehicle projects a ‘GATEway’ to success?

On this day, ten years ago (11th February 2015), on a freezing cold and windy day, I was outside the O2 Arena in London. The world’s press was assembled ahead of me and I was accompanied by two senior government ministers and the leader of Greenwich council aboard a prototype self-driving shuttle vehicle. Frankly, I wasn’t 100% sure the vehicle would behave itself but it was too late to do anything about it except cross my fingers… As technical lead of the GATEway (Greenwich Automated Transport Environment) project, I had to explain to the journalists what we were doing, why we were doing it and answer the question everyone was asking: “When will I be able to ride in one?”.

(from L-R) Vince Cable MP (then Secretary of State for Business, Innovation and Skills), Claire Perry MP (then Parliamentary Under-Secretary of State for Transport), Denise Hyland (then leader of the Royal Borough of Greenwich Council) and me - all riding on the GATEway project automated shuttle prototype. (Picture from TRL, 2015).

My recollection is that my answer was along the lines of it not being a case of ‘when?’ but ‘where?’ - highlighting how the challenges of the driving environment were likely to be a key determinant of the ability to deploy AVs. The launch event had huge coverage - even including a (career highlight!) feature in ‘Charlie Brooker’s Weekly Wipe’ (series 3, episode 4, should you wish to find it!). Brooker was not entirely enthused by the vehicles on display. That said he was more disparaging about Eamonn Holmes and his line of questions to me…

Me facing ‘tough’ questions from Eamonn Holmes on Sky News - who seemed to want an AV only if it had ‘chrome and alloy wheels’ - early insight into the user acceptance challenge for AVs! (Picture from Sky News / BBC, 2015).

Three government-supported (via Innovate UK) ‘city projects’ were being launched that day, each backed by consortia covering a wide range of capabilities:

Venturer - led by Atkins and centred on Bristol

UK Autodrive - led by Arup and based in Milton Keynes and Coventry

GATEway - led by TRL and focused on the Royal Borough of Greenwich in London

All three consortia provided example vehicles for the launch event (see below) and journalists representing the world’s press were out in force - and desperate to test the technology, insisting on stepping out in front of the GATEway shuttle whenever it trundled along its route around the Greenwich peninsula. Thankfully, it stopped in time, every time.

The journalists weren’t just there for the projects: the Department for Transport was also setting out its strategy in on AVs (2015 strategy summarised here). Reviewing this document in 2025, it is almost cute to see how naive we all were at the time (e.g. “…most commentators do not expect vehicles capable of fully autonomous operation on public roads in all circumstances to become available until at least the 2020s.”)!

Ready for their closeup! Vehicles representing the three projects launched at Greenwich in February 2015 - the Land Rover from the Venturer project; the Mondeo and two-person pod from UK Autodrive and the Meridian Shuttle from the GATEway project. (Picture by author, 2015).

The three city projects represented a government investment of nearly £20 million, with each seeking to understand how society might adapt to AVs. With hindsight, maybe there wasn’t quite the rush!? However, the projects did kickstart a raft of subsequent activity in the sector. This included providing opportunities for companies such as Oxa (formerly Oxbotica) and Fusion Processing to go from start-up to scale up and ultimately, to lay the foundations for programmes of work that led to new UK companies such as Wayve to thrive and that also encouraged global market leader, Waymo, to acquire UK capability and set up an engineering hub in Oxford.

The launch of the city projects also pre-dated the formation of the Centre for Connected and Autonomous Vehicles (CCAV) - the UK government’s policy unit dedicated to supporting growth and innovation in the AV space. Arriving in the summer of 2015, it was fantastic to have a team whose sole purpose was to facilitate the development and deployment of this technology and to coordinate the government’s actions in the area. I remember attending European meetings on automated driving and noticing the envy of international colleagues when I explained the support available in the UK.

The arrival of the UK Autodrive pod on the Greenwich peninsula - manually driven in this instance but an exciting moment! (Video by author, 2015)

The projects also prompted the creation of the Department for Transport’s Code of Practice for automated vehicle trialling - and I remember getting a slightly nervous call from the authors of the code, checking to make sure that the trials planned for GATEway would align guidance that they were planning to publish! The code of practice foreshadowed perhaps the most significant development of the last ten years on the UK AV scene: the work of the Law Commission of England and Wales and the Scottish Law Commission in reviewing the regulatory framework needed to allow AVs to be deployed on British roads. This led to the passing of the Automated Vehicles Act 2024, a critical enabler to the future regulation of AVs. It was fascinating to be a close observer (and minor contributor) to this process.

We could also point to the establishment of Zenzic and the creation of CAM Testbed UK as successes to emerge from the UK’s AV activities. In particular, I think TRL’s Smart Mobility Living Lab in Woolwich - a natural evolution of the ‘Greenwich Automated Transport Environment’ created in the GATEway project - represents a genuinely exciting and innovative facility, not just for the development of automated vehicles but as a crucible of all kinds of new transport technologies. It allows organisations to test and trial their systems in a complex urban environment with the support of advanced monitoring and communications equipment and where safety risks have been mitigated as far as is reasonably practicable. Most importantly, it allows engagement with the local residents and businesses and the opportunity to ensure that new technologies are not just accepted but actively welcomed by the communities into which they are deployed. While I, with Neil Sharpe, created the SMLL concept, I have to say TRL has exceeded the original vision to create a fantastic testbed facility that is well matched to the needs of mobility pioneers for the years ahead.

Continuing the theme of engaging the public, one of the most significant projects to be delivered since the city projects is the grandly titled ‘Great Self Driving Exploration’. This project, funded by CCAV and delivered by a consortium headed by Thinks Insight & Strategy, took a variety of automated vehicles to urban (Manchester), town (Taunton) and rural (Alnwick) locations around the UK, specifically seeking to speak to those who were unlikely to have encountered the technology before and learn their perceptions of self-driving vehicles before and after experiencing it in operation. Intriguingly, one element of the project included EEG monitoring of participants as they took their first ride on an AV and observe how initial trepidation and/or excitement subsided to calmer feelings over the course of the ride. Supporting the project as an occasional technical expert, it was fascinating to see how people in different locations perceived the technology. City dwellers were impressed but felt that self-driving vehicles were more suited to rural locations where the roads were less busy. By contrast participants at the rural location liked the technology but felt that it would never come to them and would be more suited to busy, urban environments. Early commercial deployments of AVs will have to work hard with local communities to overcome some of these preconceived ideas.

That mission of public engagement is further supported by PAVE UK (Partners for Automated Vehicle Education) - an extension of the U.S.-led international PAVE initiative. Led by WMG, PAVE UK speaks to the public and businesses on the benefits that automated driving may bring and discuss how real and perceived risks can be mitigated and to bring the AV industry together around effective common messaging. Launched in February 2024, its work is just getting started - and serving as an adviser to PAVE UK, I hope to help it succeed in its mission.

But why don’t we have automated vehicles yet?

Good question - but it depends where you look. In the U.S., Waymo’s self-driving taxi services operate in multiple cities. They have achieved an incredible amount - but at huge cost. No other western company has been able to deliver this scale of performance to anything like the same extent - and indeed many exciting companies have burned brightly but briefly over this ten year period, raising millions (if not billions) of dollars in funding but ultimately failing. These include Cruise Automation, Argo AI, Uber ATG and Ghost Autonomy. Furthermore, many traditional automotive companies who were pursuing automated driving programmes ten years ago have placed this technology into the ‘too difficult’ pile for the time being.

The optimism felt in 2015 dissipated over the years that followed - not least because of the tragic death of Elaine Herzberg in 2018, following a collision involving an Uber self-driving test vehicle. This contributed to automated driving falling into what is described on the Gartner hype cycle as ‘the trough of disillusionment’. Indeed, when I have presented on this topic, I have been questioned over whether this is not in fact an optimistic read of where we are - perhaps there is further yet to fall!?

The GATEway shuttle - we used an adapted version of the pod used at Heathrow airport to take passengers from the car park to Terminal 5. Fitted with extra software and sensors, it was capable of operating at low speeds in Greenwich outside the confines of the concrete tracks used at the airport (picture from TRL, 2015).

However, I am optimistic - as indeed is Gartner, which in its latest hype cycle has AVs moving out of the ‘Trough of Disillusionment’ and ascending the ‘Slope of Enlightenment’) - but this optimism has definitely been challenged. Excitement around AI has been a double-edged sword. On one hand, as the new ‘hot topic’, it has drawn a lot of attention, investment and talent away from the automated driving sector. However, it has also drawn away some of the ‘grifters’ - those who want to associate themselves with the latest innovations for superficial reasons rather than the genuine safety, efficiency, accessibility and equity benefits that, managed the right way, automated vehicles may bring. It feels to me that those remaining in the AV industry are there because they genuinely want to see AVs radically transform transportation for good.

However, many challenges remain. As we recognise the enormity of the task in writing hard coded rules capable of coping with complex streetscapes and scaling to multiple use cases, greater emphasis has been placed on using AI to help bridge the gap. However, automated driving as an application of AI presents major challenges for safety regulation. The lack of transparency of machine-learnt processes mean that we may be deploying systems that control high speed vehicles in public environments without certainty over how they will respond. Justifiably, you could say to me in response that we have very little certainty over human driving behaviour - and I have a lot of sympathy for that position. However, thanks to 500 million years of evolution, I can have high confidence that a human driver does not want:

…to hurt themselves

…to hurt their passengers (if present)

…to hurt other road users or animals

…to damage their vehicle

…to damage others’ property

…to risk losing their licence through breaking the rules of the road.

Of course, there are human drivers who deviate from these principles - and such deviations can result in serious injury or worse. However, given the amount of driving undertaken every day, collisions are relatively rare and if an incident does occur, it can (rightly or wrongly) be blamed on errant behaviour by an individual. Public reaction may (rightly or wrongly) be much less accepting for an AI-based system that causes a similar incident - especially if we cannot access the reasons why it adopted this errant behaviour. Certainly, some of the reactions to the presence of Cruise and Waymo vehicles in San Francisco throughout 2023 would indicate that tensions that can boil over if AVs are perceived to misbehave.

Considering how to make AVs work successfully for society speaks to the ethics of their operation. Of course, there has been a huge amount of coverage so-called trolley problems - in the event of an unavoidable collision should an AV turn left leading to outcome A or turn right resulting in outcome B - with the global Moral Machine study reported in Nature, which tested many variants of A and B and gained huge attention in the process. A further elaboration of this is the Molly Problem - an AV has a collision with a child pedestrian but no-one else is there to report it. What should happen next? These ethical conundra have helped to emphasise that self-driving technology has ramifications beyond simply making vehicles capable of driving. This was explored in further depth by the European Commission’s selected group of fourteen experts, which included engineers, psychologists, lawyers, ethicists and automotive experts and was chaired by Jean-Francois Bonnefon - one of the authors of the Moral Machine study. As a member of this group, I was very pleased that we were able to produce twenty recommendations on the ethics of connected and automated vehicles covering three topic areas: road safety; privacy and fairness and responsibility. Many of the recommendations have informed subsequent regulatory activity, including the development of the Automated Vehicles Act 2024.

Video simulation of the GATEway pod navigating through lidar point clouds of various locations in Greenwich, as part of the GATEway project (video from Oxa, 2015)

Public concern over AV safety may be ameliorated by two requirements set out in the Automated Vehicles Act 2024. That…

(a) authorised automated vehicles will achieve a level of safety equivalent to, or higher than, that of careful and competent human drivers, and

(b) road safety in Great Britain will be better as a result of the use of authorised automated vehicles on roads than it would otherwise be.

But each statement has potential problems. There is no accepted definition of ‘careful and competent’ human driving (but lots of case law of situations where drivers have fallen below the standard expected of a careful and competent driver) and no defined statistical method for proving that road safety has improved as a result of the use of AVs. Further, even if AVs are proven to be safer than human drivers, I still think public reaction will depend on the types of incident that do occur involving AVs. This has echoes of the Smart Motorway debate - even though they are continually reported as being the safest road type in terms of serious crashes, the visceral fear of being involved in a collision with a stopped vehicle in a live lane leads to a public perception that is less favourable. My belief is that the kind of transparency over AV behaviour that we gain from the Digital Commentary Driving concept that I worked on for BSI will be essential in giving assurance to the public over their true safety. Indeed, BSI’s CCAV-supported programme of work on standards (including the BSI Flex 1890 CAM Vocabulary, for which I have served as the technical author on all five iterations to date) has created a fantastic community of practice, working together to ground the UK’s AV activities in a common language and understanding about the development and deployment of self-driving technology.

So what of the next ten years?

Though I am more circumspect in 2025 than I was in 2015, I am still excited by our future with AVs. I would be surprised if, by 2035, AVs were the majority of vehicles on UK roads. However, I would also be surprised if there weren’t a significant proportion of vehicles that at least enabled a driver to divert their attention away from driving for lengthy periods under certain conditions. This means of course that we will need to have addressed the challenges of transitions between automated and human control but there are many very smart human factors people working on this topic (Natasha Merat, Mike Lenne, Liza Dixon, Marieke Martens, Nicole Van Nes and Clare Mutzenich to name but a few).

We will also see the expansion of automated vehicles operating seamlessly in constrained environments - ports, airports, mines, guideways. Whilst this happens to some extent today, a further evolution will be characterised by a shift towards more and more sophisticated use cases where AV software developers do not need to adapt their systems for each deployment. Simplified user interfaces will allow customers to take control of the software to get AVs delivering the services they desire and only seeking dedicated support when absolutely necessary.

And what about more exotic forms of automated driving? Well, we know that, in addition to further expansion within the U.S., Waymo has identified Tokyo as a first toe into the water of international expansion in 2025. One can imagine that, if they have tackled regulatory requirements in multiple territories and can handle complex urban driving conditions on either sides of the road, success in Japan would open the door to expansion across many different markets. By contrast, as we have seen with DeepSeek, could a plucky underdog suddenly emerge as a global competitor? Maybe that underdog come from the UK? It’s not inconceivable - but for me, however we can get robustly proven lifesaving technology onto the roads as quickly as possible, I’m all for it. This might mean discomfort for some in the industry as we get used to the transparent sharing of data in the interests of safety - but ultimately, i believe this will be necessary to gain trust and acceptance from the communities where these vehicles will operate.

To challenge a well worn cliche, the road to automated driving is not a sprint. It’s not even a marathon. In fact, it is not even a race! It doesn’t have a defined start or end but represents one facet in the ongoing evolution of our transport system. We must be sure to shape it so that it truly serves society and not just those seeking a return on their investment. I doubt Eamonn Holmes’ wish to own an AV bedecked with chrome and alloys will be fulfilled in the next ten years but, as he pushes into his seventies, and beyond, I hope there are automated transport options available to him (and to all of us) that sustainably meet our mobility needs. Maybe 2015 was indeed a ‘gateway’ to the future of transport after all…