A sunny trip to Capri – the (driverless) car you always promised yourself?

On a warm and sunny Friday in September, I made the trip to the Queen Elizabeth Olympic Park site in Stratford, London to see the self-driving shuttles being trialled there as part of the Capri project. Capri is led by engineering consultancy, AECOM, in a consortium of 19 partners funded by UK Government and industry. I took my Brompton on the train to Waterloo and enjoyed a very pleasant ride along Cycle Superhighway 2 and the River Lea to the location. These trials were of particular interest to me, having led the GATEway project that successfully trialled similar vehicles in Greenwich between 2015 and 2018 – with vehicle manufacturer Westfield the common participant between the two projects.

The London Stadium and ArcelorMittal Orbit

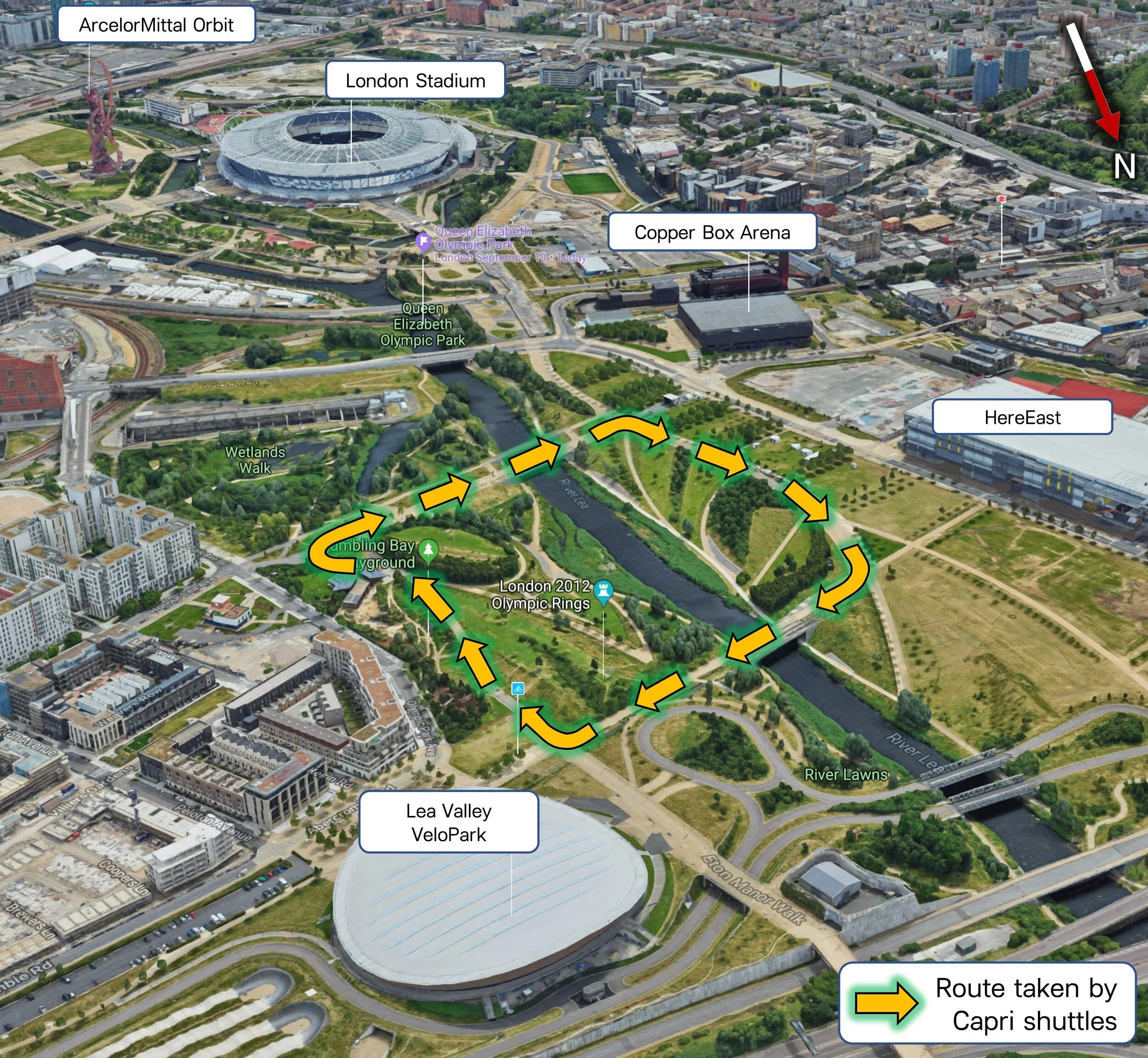

On arriving, I cycled around the stadium (now home to West Ham United Football Club) and the ArcelorMittal Orbit structure designed by Anish Kapoor. However, the shuttles were operating to the north of the Olympic Park site in a loop near the velodrome (the Lea Valley VeloPark - affectionately known as ‘The Pringle’ due to its striking appearance that hints at the banking of the indoor cycling track).

Capri Shuttle navigating the trial route (with ‘The Pringle’ – Lea Valley VeloPark in the background)

Making my way to the velodrome, I was rewarded with an unexpected bonus. Two familiar looking blue Ford Mondeos caught my eye parked outside the velodrome, one of which had an array of sophisticated roof mounted equipment – giveaway characteristic of current automated vehicles. Indeed, these were two vehicles from automation software company, Oxbotica – with whom I worked on the GATEway project. The Mondeos are participating in the Driven project, which will see SAE Level 4 automated driving in London before the end of the year. The Mondeos soon set off mapping various routes in the area that will be part of their upcoming launch event.

Oxbotica vehicles ready for mapping duties outside the Lea Valley VeloPark

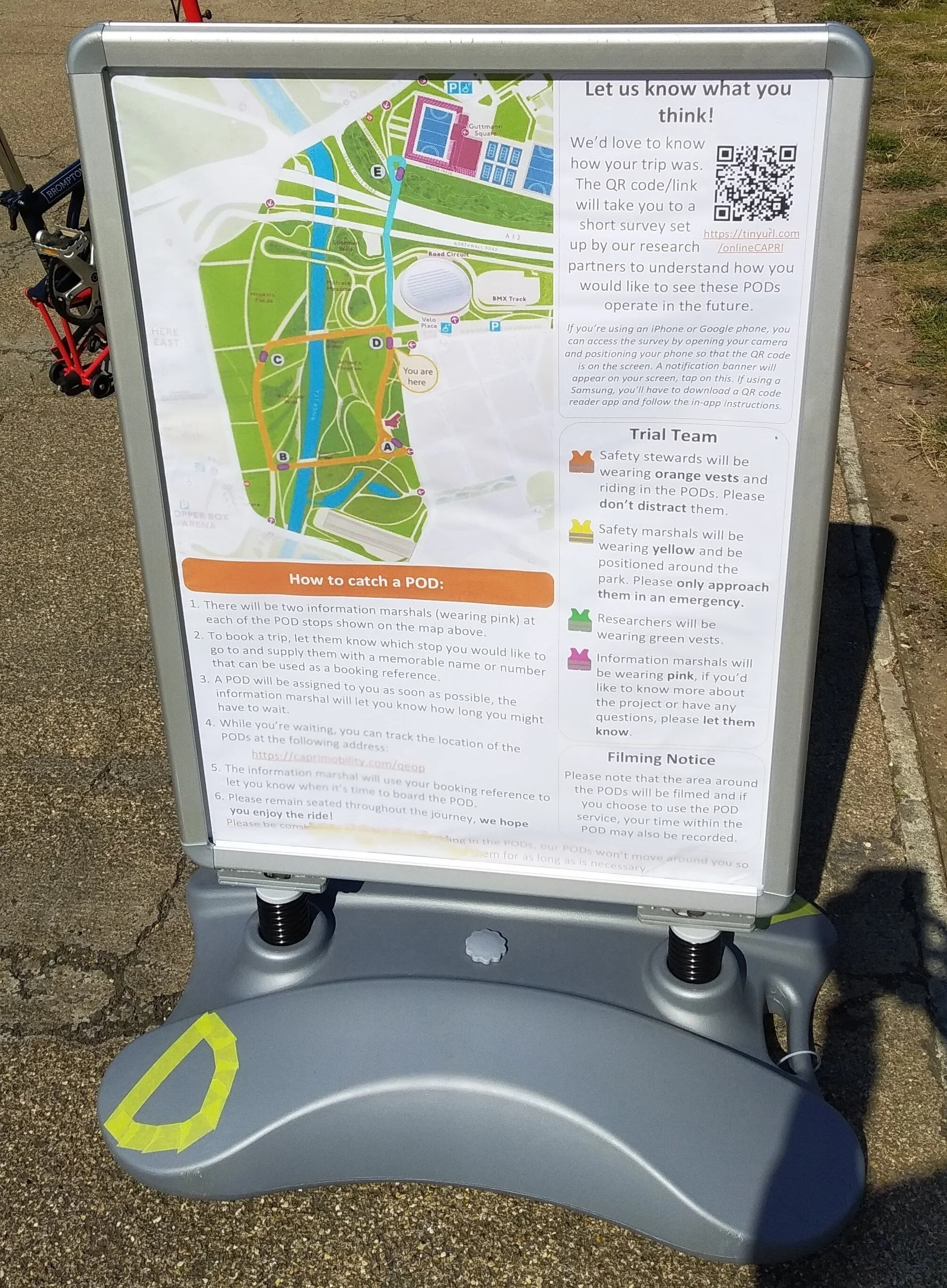

Returning to the Capri project, I noticed small, temporary boards indicating the stops for the shuttles. One of the friendly marshals told me that a shuttle would arrive in ten minutes so I could wait at the stop. However, I decided to follow the route on my bike and find the shuttles for myself. Sure enough, I arrived at the operations centre where the shuttles ‘rested’ whilst the marshals and trials operatives had stopped for lunch. This gave me an opportunity to get up close to the two shuttles and explore the similarities and differences between the GATEway shuttle and these newer models.

Information boards at designating Stop D on the Capri shuttle route

A few major differences stood out from the GATEway shuttles. In the GATEway project, Westfield produced the vehicle based on the Heathrow UltraPRT pod but the automation systems were provided by other partners. In Capri, Westfield have stepped up to produce the vehicle and integrate the subsystems and software required to enable self-driving operation. The first change is the sensor array – with additional ultrasound and radar sensors and lidar / camera systems now neatly packaged into units dotted around the vehicle.

Front of Capri shuttle Bremer – note the multiple camera / lidar pods, low mounted exposed radar and shielded ultrasound sensors

Secondly, one of the vehicles (Brabazon 2) has been adapted with larger wheels and a higher ride height, requiring modestly flared wheel arch trims. Although this looks slightly ungainly compared to the original design, there is no doubt that for real world urban applications, the new arrangement will be more practical, giving better ride quality and greater scope to deal with surfaces that are less than smooth. However, it does mean that the step up into shuttle is higher, which might compromise accessibility.

Brabazon 2 (foreground – higher ride height) and Bremer (background – lower ride height) shuttles ready for duty at the Queen Elizabeth Olympic Park

A further change is in the vehicle interior with four individual seats rather than the bench seating used in the GATEway shuttles. Whilst the bench seats offer more flexibility in accommodation, the fixed seats provide greater comfort and enable full three-point safety belts to be fitted for the occupants.

Individual seats with integrated safety belts in the Capri shuttles.

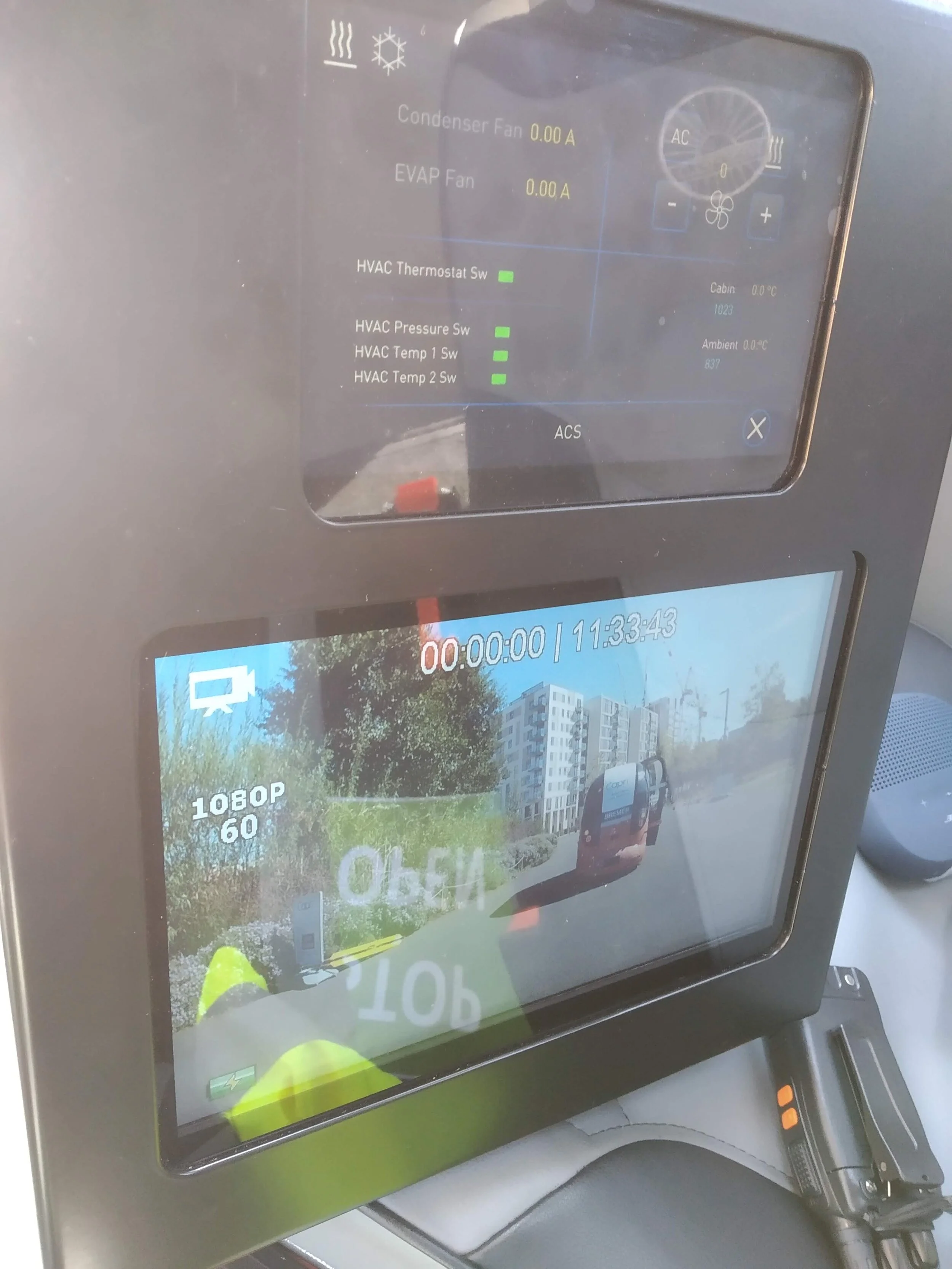

Safety steward’s control / display panel within the Capri shuttle

The break also meant I could talk to the project team about their experiences. It was immediately apparent how much they loved being involved in the venture; all were passionate, knowledgeable. and justly proud of successfully delivering the vehicle trials. However, and as often happens, it was apparent there have been one or two compromises and challenges along the way that have caused the project to evolve from its original vision.

After lunch, the shuttle service resumed. The route taken by the vehicles is a relatively short (approx. 1.2km) square lap of the wide pedestrian walkways in the northern Olympic Park site and takes in the Olympic rings – a pleasing reminder of London 2012. One of the shuttles required some manual repositioning in order to lock itself back onto the ‘breadcrumb’ trail that it uses to navigate the route – but once located, it was ready for operation.

Trial route of the shuttles at the Queen Elizabeth Olympic Park in the Capri project (Map data: Google, Bluesky, Getmapping, Infoterra Ltd, Bluesky, Maxar Technologies, The Geoinformation Group)

As you will see in the videos below, the shuttle was cautious and goes no faster than walking pace. Of course, this invites the challenge as to why anyone able to walk would not choose to do so. However, a 5mph speed restriction applies to vehicles within the park grounds so this is a limitation of the environment rather the technology.

Capri shuttle making its way around the test route with the Olympic rings in the background.

Westfield CEO, Julian Turner, enjoyed showing his ‘party trick’ of laying in front of the shuttle to demonstrate its ability to detect low hazards.

I cycled alongside one of the Capri shuttles during their trials at the Olympic Park when the collision detection features were being demonstrated

I cycled back towards central London reflecting on what I had seen. I was certainly impressed by the achievements of the team. I know full well how challenging it can be to take an innovative transport system into a public environment for trials. I was also proud to see the various automated vehicle trials taking place within the Smart Mobility Living Lab - demonstrating the value of this concept that I helped to create whilst at TRL.

However, there’s certainly more to do to realise the benefits of automated driving. When considering developments from the GATEway project, I envisaged three areas where follow on projects should progress:

Move to vehicle operations without a safety steward on board

Shift to commercial operation with customers summoning vehicles and paying for trips through an app

Operate on public roads in live traffic

The Capri project has given demonstration runs with a remote safety steward and I gather there could be on-road trials next year (though these may be closed private roads) but I can’t help but feel that for all the investment and effort being made, we (the UK CAV sector) are not moving the game on enough; that proofs of concept, short term demonstrations and limited off-street trials are not fulfilling either the promise of CAVs offered by the industry five years ago nor the expectations of the public for whom CAVs may offer safer and more efficient transport services.

I hope that all of the fine work that has gone into delivering the Capri project can provide a platform from which commercially sustained and socially beneficial services can emerge. However, in this time of political uncertainty in the UK, it is a good time to reflect on the fine principles set out in DfT’s Future of mobility: urban strategy and excellent recommendations from the CREDS team in their report ‘Shared Mobility – where now, where next?’, and consider whether we have the correct balance of investment in transport systems to achieve the best environmental, societal and commercial outcomes.

I am very grateful to the Capri team who were generous hosts of my impromptu visit to their trials. I am also impressed by what they have achieved. I know that managing the interests and concerns of a large number of stakeholders within and outside the project consortium in preparing and delivering automated vehicle trials is a tremendous undertaking and one that they have tackled with enthusiasm and grace. I wish them well in the final stages of their project and hope that it provides the foundations for future success.