CAVs and Kindness

“I have found that it is the small everyday deed of ordinary folks that keep the darkness at bay. Small acts of kindness and love." (Gandalf; J. R. R. Tolkien, The Hobbit)”

I was fortunate enough recently to be attending an early afternoon meeting in Sussex. I grew up in this region of England and enjoyed the familiar feel of its rolling hills and winding tree-lined country roads. Sadly, public transport options to get to the rural meeting venue were lacking. Google suggested the train and bus route would take two hours and fifty-five minutes against a drive of one hour and twelve minutes. I took the shorter option.

Driving is not my favourite activity but outside of peak travel time and with no urgent time pressure it is far more agreeable. Given this relaxed mode, I noticed my approach to driving was similarly calm. To my mind, this was characterised most conspicuously by a greater willingness to allow others to pull in / pull out. This trait of greater kindness struck me as interesting from the perspective of connected and automated vehicles (CAVs). To what extent does traffic flow depend on (or suffer from) altruistic acts by obliging drivers and will kindness emerge as a behaviour when computers are in charge? As drivers, we can intuit the intentions of other road users. We can understand that sometimes we might need to rely on a kindly act from another driver to allow us to pull out at a junction so it makes sense for us to act similarly charitably from time to time. Will automated vehicles develop a theory of mind such that they can understand intentions of other road users? Will they be able to show Gandalf’s recommended small acts of kindness and love?

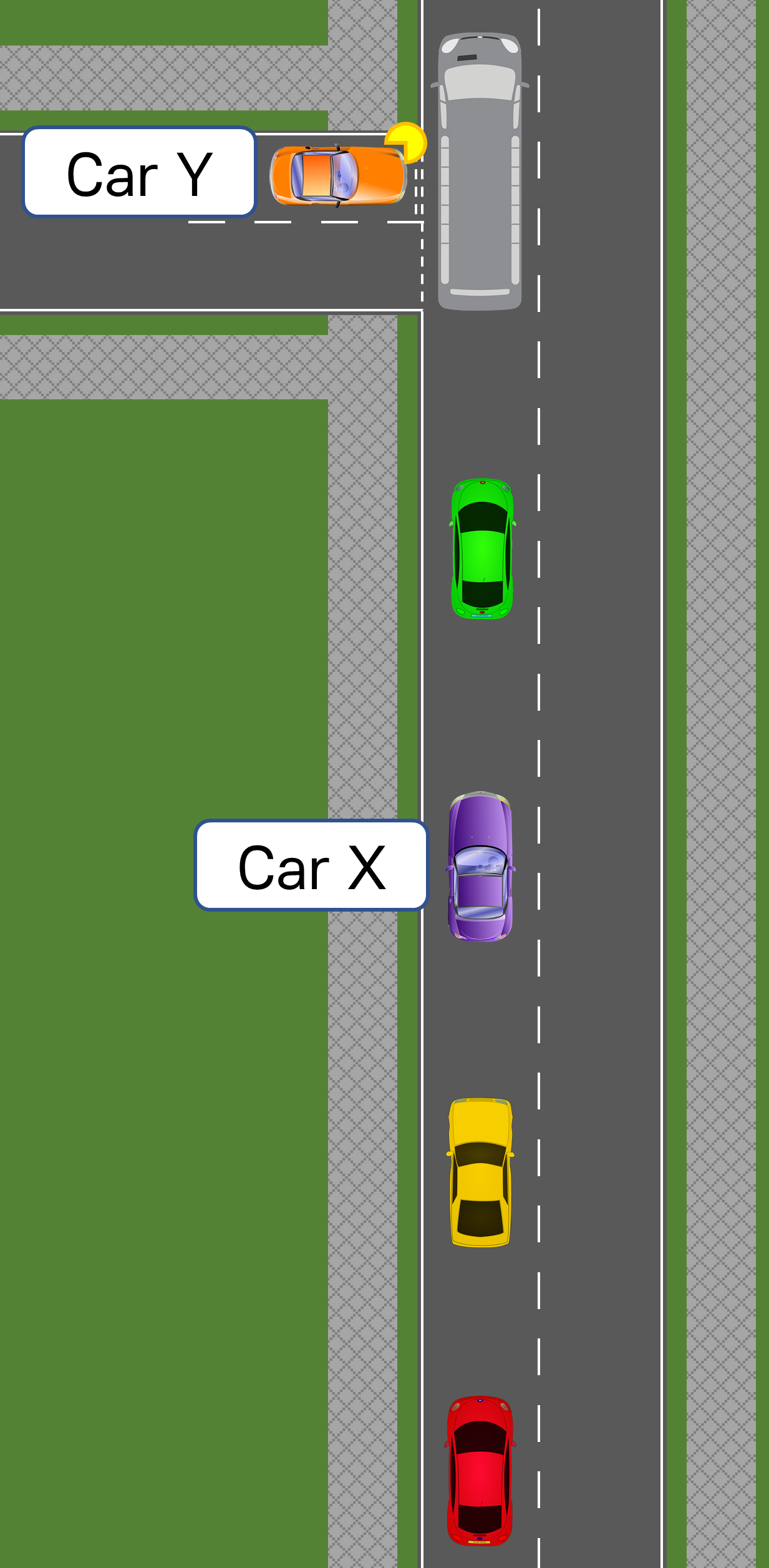

Cooperative driving behaviours can come in many forms. Some are specified in the UK Highway Code (e.g. rule 163 “give way to oncoming vehicles before passing parked vehicles or other obstructions on your side of the road”) and it is relatively straightforward to understand how such rules could be codified in a CAV. Other such behaviours simply emerge from individual drivers understanding the challenges others are facing in completing their onward journey. For example, driver A in Car X sees Car Y trying to pull out of a side road into an endless queue of traffic – driver A realises that it would be helpful to allow Car Y to pull out, even though it causes some delay to driver A (and all vehicles behind Car X).

Car Y seeking to pull out of a side road into traffic. The driver of Car X may choose to allow Car Y to pull out.

What if Car X were a CAV (assume SAE L4 operation)? By communicating with a central traffic coordination system, Car X may receive information to say that it should slow to allow car Y to pull out. Although this might cause some non-trivial delay to Car X’s journey (and all vehicles behind Car X), this may minimise overall delay in the traffic system – for example, by reducing delay to Car Y and all vehicles behind Car Y. This optimisation task would be made easier if Car Y were a connected car but the decision could be based on the Car X’s sensor-based perception of Car Y and / or any traffic monitoring data related to the relevant vehicles and roads. These cooperative behaviours are therefore underpinned by data – the better our understanding of traffic situations and the impact of individual behaviours within the traffic system, the more effectively we can manage the journeys of vehicles using that system.

This logic could be applied to help situations where observed human driving etiquette can harm traffic flow. When a motorway lane closure causes congestion, it is common to see vehicles moving over to the open lane early. However, simulation and observational studies have shown that in some situations, merging in turn at the point of the road closure helps to maximise the use of available road space and reduces the overall impact of the congestion. CAVs could reduce congestion and improve journey time reliability by adopting optimal strategies on the approach to roadworks. The UK Department for Transport sponsored engineering consultancy Atkins to produce a report on CAV effects on traffic flow finding minimal effects at low market penetration but significant benefits as the proportion of CAVs in traffic increases.

Returning to the situation with Car X (CAV) and Car Y – and assuming Car Y is not a connected car – how should Car X signal to Car Y that it is allowing Car Y to pull out? In the UK, a customary technique for indicating that you are yielding to another vehicle is to flash the headlights. However, this signal is informal and not specified in Highway Code. Furthermore, it has different meanings in different countries and in some situations can result in dangerous situations. My sense is that rather than try to adopt any new form of communication system, Car X’s kinematic behaviour would be the best way to signal that it is allowing Car Y to emerge. If Car X decelerates conspicuously ahead of the side road, the driver of Car Y can choose to accept the gap or not. Gustav Markkula and colleagues at the University of Leeds Institute for Transport Studies produced fascinating work showing that a vehicle can effectively communicate its intentions to pedestrians waiting to cross by displaying suitable deceleration behaviour whilst also minimising overall traffic delay.

We could imagine Car X’s propensity to act altruistically as an adjustable setting based on the preferences of the user. If the user has chosen to optimise their journey for speed or for energy efficiency, Car X’s willingness to accept delays and inefficiencies caused by accommodating the behaviours of other vehicles (such as Car Y) may be lower. However, I may have to pay extra to a CAV service operator and / or a traffic coordination organisation for this feature. Conversely, I may be rewarded somehow if I am willing to allow my vehicle to accept delays in such a way that it helps to maximise overall network efficiency. Taking this further, one could imagine a premium service whereby my CAV can assert priority over other connected vehicles and where its progress is facilitated preferentially at traffic light controlled junctions. This is like priority check in at airports for First / Business class travellers – by paying extra for premium ticket, your journey through the airport and onto the aircraft is accelerated.

The automotive journalist, Alex Roy, has written passionately against this idea seeking to maintain what he calls traffic neutrality. Like Alex, I am uncomfortable with the idea of premium routing in traffic and appreciate the democratic nature of our roads but offer a couple of further thoughts. Firstly, that emergency vehicles should be granted this ability to assert priority for obvious reasons. Similarly, traffic optimisation strategies could also work to provide public transport vehicles with an advantage, helping them to provide an efficient, reliable service. This would be a natural extension of traffic signal bus priority schemes that have been used in the UK for more than fifteen years. Secondly, that I may be willing to accept others paying for premium trip optimisation services if:

ultimate control over the parameters of such services sits within the public sector;

they are monitored to ensure that implementation does not unfairly delay non-users;

fees paid for the service do not go exclusively to private sector operators of the scheme but can be used by the public sector to increase the efficiency and sustainability of existing transport networks. The revenues generated could be used to support the funding of new cycle infrastructure or used to subsidise local bus services.

The complexities of the interactions between CAVs, human drivers and other road users lay at the heart of why the anticipated CAV revolution will longer than was previously anticipated. No previous situation has seen machines interacting so extensively with humans in such a complex task and with such high risk consequences in the event of mistakes or failures. Ultimately, CAVs will need to behave cooperatively in order to deliver efficient road transportation. Whilst these cooperative behaviours may be perceived as kindness, the slightly sad truth is that, in reality, they will simply be part of the optimisation of a dynamic traffic situation. The challenge therefore is to ensure that this optimisation is managed fairly and supports the transition towards sustainable transportation. At least as passengers in automated vehicles, we can use the time to find other ways to show Gandalf’s acts of kindness and love that will keep the darkness at bay.